Chapter 13

Female Hormonal Contraceptives

A functional account about progestogens, androgens

and oestrogens has already been given in Chapter 5. It included the metabolic,

morphological and endocrine effects of these three different steroids. It will

be an impossible task to write about all brands of the hormonal contraceptives

available worldwide. Many good brands are licensed in certain but not other

countries. Accordingly, this chapter is not meant to give a detailed account of

such different variations, or the instructions on how to use different

contraceptives. It is written with the following objectives in mind, avoiding

repetition of previously discussed issues:

- A broad

account of the different types of female hormonal contraceptives and their

mode of action;

- The

non-contraceptive benefits of hormonal contraceptives;

- Use of

hormonal contraceptives by patients with known medical problems;

- Complications

and risks of hormonal contraceptives;

- Emergency

contraception;

- Perimenopausal

contraception.

Types of

hormonal contraceptives and their mode of action

Despite the great advances in the field of family planning

over the last 30 years, oestrogens and progestogens remained the cornerstones

for hormonal contraceptives, though newer means for their delivery have been

introduced. Beside the oral route, transdermal, transvaginal and intrauterine

routes have been used effectively, and with great acceptance by women.

Progestogens played the major part in hormonal

contraception, and are mostly derived from three parent steroid molecules which

are estranes, gonanes and pregnanes. These molecules differ in relation to

their half lives, and their antioestrogenic effect. Furthermore, gonanes have

17 carbon atoms, whereas estranes have 18. The range of progestogens used

includes norethindrone, norethindrone acetate, ethynodiol diacetate,

norgestrel, levonorgestrel, norethynodrel, desogestrel, norgestimate, and

gestodene. The last three are derived from the gonane molecule, and are known

as the third generation progestins. Other gonane derivatives include norgestrel

and levonorgestrel. Estranes include norethindrone, norethindrone acetate,

ethynodiol diacetate, and lynestrenol. Pregnanes include medroxyprogesterone acetate and megestrol acetate, and they have no

androgenic activity. They are used in the injectable forms of hormonal

contraceptives. The sequence of ascending androgenicity of the different

progestogens used is: ethynodiol diacetate, norethindrone, norethindrone

acetate, norgestimate and desogestrel, in that order. Levonorgestrel and

gestodene have the highest androgenicity in all groups. This information is of

great value when selecting a specific brand of contraceptive pill, especially

when dealing with hyperandrogenic patients. Furthermore, progestogens of lower

androgenic capability are less likely to oppose the oestrogen induced hepatic

production of sex hormone binding globulin and high density lipoprotein (HDL).

A new spironolactone analogue (drospirenone) which has

anti-mineralocorticoid, anti-androgenic and progestational activities has been used in oral

contraceptive pills, mainly for women with polycystic ovary syndrome and

premenstrual dysphoric disorder.

In contrast to the long list

of progestins, only two oestrogens are used in the majority of combined

hormonal contraceptives; ethinyl oestradiol and mestranol. Ethinyl oestradiol

is pharmacologically active, whereas mestranol has to be converted into

oestradiol first before gaining biologically activity. Oral contraceptives

currently in the market contain 20 - 35 micrograms of oestrogen. Pills with 50 µg

ethinyl oestradiol are still available, but are used for the management of

certain gynaecological problems when high doses of oestrogen are needed, rather

than for regular contraceptive purposes. Unlike all the

other routes, orally taken ethinyl oestradiol is

absorbed rapidly from the intestines and undergoes rapid metabolism in the

liver during the first hepatic pass which reduces its biological efficacy by almost

40%. It has plasma half life of 10-27 hours, with a

longer half-life in tissues, such as the endometrium. This first hepatic pass affects different liver functions, including

increased production of clotting factors, sex hormone binding globulin,

transcortin, thyroid binding

globulins, as well as changes in the lipid profile. This may have direct

positive or negative effects on different individuals, depending on their own

circumstances, such as patients with hypothyroidism on thyroxine replacement

therapy. Such hepatic first pass does not occur with the transdermal route,

which can be of benefit especially for patients at risk of thromboembolism.

Hormonal contraceptives can

be used in different forms:

Oral contraceptives

Oral contraceptives can be used either in a combined

oestrogen and progestogen form, or as progestogens only pills. Regular brands

of the combined form have 21 pills, either in monophasic, biphasic or triphasic

combinations. Monophasic pills have the oestrogen and progestogen in a fixed

dose in the same pill for the whole 21 days. Biphasic and triphasic brands have

oestrogen and progestogen pills in two or three different doses to be taken in

sequence respectively. The idea behind these different combinations was to

reduce the total amount of hormones used, and to simulate the variations in

oestrogen and progesterone which occur during a natural ovulatory cycle. Newer

brands of oral contraceptives have been manufactured to reduce the hormone free

period by increasing the number of pills to be taken each cycle. Brands with 24

or 26 instead of 21 pills have been marketed. The main objective behind this

regimen was to have better control of the bleeding episodes, and to reduce the

premenstrual symptoms suffered by the patients during the hormone free period.

Such brands are sold in the United States, but are not licensed yet in the

United Kingdom. An extended protocol to use oral contraceptive pills for 84

days before having a withdrawal bleeding proved useful for patients with

endometriosis and severe premenstrual syndrome. Seasonale

(Duramed Pharmaceuticals, Inc) is a brand which contains 30 µg ethinyl

oestradiol and 150 µg levonorgestrel. Yet again, despite the wide increase in

the number of brands of combined hormonal contraceptives currently available,

suppression of ovulation and local uterine changes remained to be the most

important modes of action. These are affected through the synergistic effects

of both oestrogen and progestogen. Nonetheless, in most cases the contraceptive

efficacy is linked to the progestogen part, with oestrogen controlling regular

bleeding.

Unlike oestrogens, progestogens can be used

separately to provide adequate contraception. Progestogens only pills have been

available for a long time, and are sometimes known as mini pills. They are

mainly used when oestrogen is contraindicated. This is especially so in cases

at risk of cardiovascular diseases and venous thromboembolism. They are also a

good choice for lactating women requiring contraception, as they do not affect

milk production, and do not influence the infant’s growth or development.

Unlike the combined forms, they should be used continuously and at the same

time every day without a break. Different brands are available and their main

contraceptive effects have been related to the following points:

· They increase cervical mucus

viscosity which reduces transcervical sperm migration into the uterine cavity.

This effect is maximal four hours after intake. The pills should be taken at

the same time every day, as serum levels fall to baseline levels within 24

hours after ingestion. Other precautions should be taken for 48 hours if taking

a pill is delayed for more than 3 hours.

· They can inhibit activation

of the enzymes necessary for sperm capacitation which is required for ovum

penetration.

· They slow ovum transport

through the fallopian tubes, which may increase the risk of tubal pregnancies.

· They reduce embryos

implantation due to their progestational histological effects on the

endometrium. Progestogens deplete their own receptors and oestrogen receptors

in the endometrium. Biochemically, progestogens reduce the production of

glycogen in the endometrium, and accordingly reduce the ability of the

blastocyst to survive in the uterine cavity.

· Small doses of progestogens

as used in the progestogen only pills do not usually inhibit ovulation, and

many women continue to ovulate normally. Occasionally, only the LH surge is affected despite growth of

the follicles to a mature size. This explains the increased risk of functional

ovarian cysts seen in patients using

progestogen only pills.

Injectable

contraceptives

The two main injectable forms are

depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (depoprovera) and combined injectable

contraceptives (CICs), both being long acting contraceptives.

Depoprovera can be used in a dose of 150 mg every 3 months. Its blood level

peaks approximately 10 days after drug administration, and sustain high blood

levels capable of inhibiting ovulation by direct action at the hypothalamus and

pituitary gland. It also has a strong progestational effect at the level of the

endometrium. Amenorrhoea is common after the third dose in almost 50% of the

users, with the majority of the remaining group having irregular bleeding

episodes (1). After one year of use, about 75%

of the users will be amenorrhoeic. It may take up to 200 days for the drug to

clear off the circulation following a single injection, as documented in the

Depoprovera Product Monograph (2). This slow decline in the level of serum

progestogen is responsible for the long period of amenorrhoea and delayed

return of fertility. It took 9 months after the last injection on average for

women to conceive as reported in the same Monograph (2).

In comparison to intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUCD) and oral

contraceptives, 92% of women conceived within 2 years after discontinuing

depoprovera, 93% after IUCD

and 95% after stopping the pill (2). Partial

reactivation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-ovarian axis may allow basic folliculogenesis to restart

leading to development of mature follicles, with failure of the LH surge mechanism. This will prevent the final act of

ovulation, or may lead to abnormal ovulation and dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Being a strong

antioestrogen, it has been associated with the development of osteoporosis. This effect has been quantified

by the Product Monograph alluded to before (2), which reported 5-6% reduction in the spine and hip

bone mass density after 5 years of depoprovera use. This decline was more

pronounced during the first two years of medication. This effect was not

carried through during the postmenopausal years as shown by a World Health

Organisation study, which showed similar bone mass density in women who did or

did not use depoprovera (3). Furthermore,

young women in their teenage years are more likely to regain their bone mass

density within 12 months after stopping medication. An advantage of depoprovera

is that it has no androgenic effect. Furthermore, it does not affect the level

of triglycerides or total cholesterol (4), and has no significant detrimental effect on the liver

function, coagulation factors, fibrinolysis, or blood pressure.

Alterations in carbohydrate metabolism similar to those imposed by the oral

contraceptive pill can follow depoprovera administration, but to a lesser

extent and with minor clinical significance (5). More information about depoprovera has been

given in Chapter 5. Another injectable progestogen is Noristerat, which is made

of 200 mg norethisterone enanthate. It should be given by deep intramuscular

injection on the fifth day of the cycle for short term effective contraception,

when patient’s compliance is not guaranteed regarding the pill. It can be

repeated after eight weeks if necessary. It has similar mode of action to

depoprovera, but menstrual irregularities are less common.

Combined injectable contraceptives (CICs) contain

both oestrogen and progestogen, and are given by monthly intramuscular

injections. Their mode of action is similar to that of the combined oral

contraceptive pill, with similar range of side effects and contraindications,

but without the first hepatic pass. They offer better cycle control

and quicker return of fertility after suspending medication than the

progestogen only injections. There are three main types of

CICs including Cyclofem, Mesigyna and Deladroxate. Cyclofem (cyclo-provera)

contains 25 mg depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate, plus 5 mg

oestradiol cypionate. Mesigyna is made up of 5 mg oestradiol

valerate and 50 mg norethisterone enanthate. Deladroxate contains 10 mg

of oestradiol enanthate and 150 mg dihydroxyprogesterone acetophenide. The

first dose should be given within the first 5 days of menstruation, and repeat

injections administered every 28 days. They offer an error margin of 5 days

only. Because of their depo effect, ovulation and fertility usually return 2-3

months after the last administered dose (6). A

recent Cochrane database systemic review showed that more women using CICs had

normal bleeding, and

fewer of them stopped using them because of bleeding reasons than

progestin-only users (7). Another

advantage of CICs is that there is low incidence of amenorrhoea, after their

prolonged use. Despite all these advantages, this method is not very popular

yet, and is not licensed in many countries. Nevertheless, it can be very useful

in developing countries as it needs less compliance than the oral contraceptive

pill.

Subdermal contraceptives

Research in subdermal implants

started in 1967 which resulted in the introduction of Norplant in 1983 in Finland, before being used in other

countries. It was licensed for 5 years, but has been withdrawn from the UK in

1999. Another discontinued brand was Jadelle,

which was made of two rods each containing 75 mg levonorgestrel. The only

licensed brand in the UK now is Implanon, which is a single subdermal 4 cm rod with 68 mg etonogestrel

dispersed in ethylene vinyl acetate core. It is covered by 0.06 mm

rate-controlling membrane. During the

initial stages, it releases 60 - 70 µg/day, which declines to 25 - 30 µg/day by the end of the third year. It is licensed to be used for 3 years after insertion, and

should be inserted subdermally usually in the upper arm under aseptic

conditions. The same incision used for removing the old rod can be use to

insert the new one. It has the same mode of

action as depoprovera, and almost similar indications as well. There is also increased

risk of irregular uterine bleeding, which makes the commonest cause for

removing the rod. In all, good cycle control was reported by only 28% of women

over a period of 3 years (8). Other statistics showed

30-40% amenorrhoea throughout the 3 years, 30% infrequent bleeding and 10-20%

prolonged bleeding episodes. Its contraceptive and cycle control

efficacy is decreased if

hepatic enzymes inducing drugs such as rifampin, carbamezapine, phenobarbitol

and St. John’s Wort are used at the same time.

Transdermal contraceptives

In

recent years transdermal combined oestrogen and progestogen contraceptive

patches became available. They have the same mode of action and efficacy as the

combined pill, regarding suppression of ovulation, cycle control and cervical

mucous viscosity (10). They have an extra advantage, as the absorbed hormones do not pass

through the liver first. This reduces the production of all oestrogen dependent

hepatic factors, which occurs following the first pass through the liver. A

once-weekly Evra patch (Janssen-Cilag Ltd) can be used for 3 weeks

starting on the first day of menstruation, followed by one patch-free week.

Each patch delivers 33.9 µg ethinyl oestradiol and 203 µg norelgestromin daily

into the systemic circulation. To reduce the risk of ovulation the patch should

be changed every 7 days irrespective whether menstruation has not started or

bleeding has not stopped yet. A new patch may need to be replaced in less than

2% of the cases because of complete detachment. Contraindications for using

combined oral contraceptives are valid for the patch as well. Furthermore, one

follow up study showed that women younger than 20 years of age were less likely

to use the patch properly, compared to the contraceptive pill (11). This method is

more suitable for women in their twenties or thirties who are not very

compliant with the daily routine of the oral contraceptive pill, and are not

keen on other methods.

Intrauterine

devices

1. The mirena system (Bayer) is a levonorgestrel impregnated

intrauterine system which is becoming widely used for contraceptive purposes,

as well as for control of excessive menstrual blood loss. It is made of a

polymer cylinder containing 52 mg of levonorgestrel mounted on a T-shaped

frame. It releases 20 µg of levonorgestrel every day into the uterine cavity,

through a hormone rate limiting membrane covering the device. It acts as a

contraceptive through the same 4 mechanisms described for other progestogens

earlier on in this chapter. It does not inhibit ovulation in the majority of

cases. There is occasionally an initial period of abnormal uterine bleeding

which usually settles within 3 months. Patients should be counselled

accordingly to prevent unnecessary premature removal of the device. Eventually,

the amount of blood loss and bleeding days will be reduced, and 20% of women

may become amenorrhoeic after one year (12). This

beneficial effect has been used to avoid surgery with reasonable results in patients with uterine fibroids. Few

studies showed reduction in blood loss and regression of the uterine size, with

or without diminution in the fibroids mass (13, 14).

This effect was thought to be secondary to inhibition of the endometrial growth

factors. Nevertheless, such devices can be used only when the cavity is not

significantly affected by any fibroid. The system is licensed for 5 years

following its insertion into the uterine cavity. Unlike cupper containing

intrauterine contraceptive devices, it is not licensed for postcoital emergency

contraception.

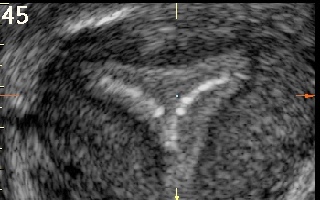

The mirena system has

no metal component and accordingly different ultrasound characteristic to CuT

devices, but still more echogenic than a Vcu200 device. Figures 42 - 44 show sagittal uterine transvaginal ultrasound views

with a CuT device, mirena system and Vcu200 device correctly sited inside the

cavity respectively. Note the progressively softer echogenic patterns created

by the mirena system and Vcu200 device compared to the sharp echo created by

the CuT.

When available, 3D

ultrasonography can be helpful in showing the exact type of IUCD, especially

with the less commonly used and less echogenic Vcu200 device.

|

|

|

Figure 45

is coronal transvaginal ultrasound scan of a uterus with a normal triangular cavity and Vcu200 contraceptive device in situ.

|

Intravaginal contraceptives

Vaginal rings with

combined oestrogen and progestogen, and progestogen only medication are gaining

popularity as reversible contraceptive means in certain parts of the world. One

example of a combined oestrogen and progestin ring is NuvaRing (Schering), which is available

in the United Kingdom market. It is a flexible one size ring (54 mm) made of ethylene

vinylacetate copolymers and magnesium stearate. It

liberates 15 µg ethinyl oestradiol and 120 µg etonorgestrel daily into the

vagina. It should be inserted into the vagina on the first day of menstruation

by women who did not use hormonal contraception in the preceding cycle. On the

other hand, women who are using any form of combined hormone contraception can

switch to use the ring on any day, the latest being the day following the usual

hormone free interval. It can be used for 3 weeks, followed by seven ring-free

days every month. Personal application is easy by squeezing the ring during its

insertion into the vagina, while squatting, lying down, or with one leg lifted

up on a chair. It does not need to stay in any specific shape or position

within the vagina. Its mode of action is similar to other combined

contraceptives. The ring can be removed for cleaning but replaced within 3

hours to maintain proper contraception. Good cycle control was reported by 98%

of users (15). Nevertheless, 2-5% reported device-related problems including

vaginal discharge, vaginal discomfort and problems during intercourse in the

same study. This last problem can easily be overcome by removing the ring

during intercourse, but replacing it immediately thereafter. The grace period

for changing vaginal rings is longer than for transdermal patches. Accordingly,

one ring can be used continuously for 4 weeks, and changed immediately on the

same day after that with a new one, to avoid onset of menstruation if

desirable. Leaving the same ring in the vagina for more than 4 weeks reduces

its contraceptive efficacy, as advised by the manufacturer’s patient

information sheet. There is also a small risk that NuvaRing can be accidentally

expelled from the vagina during intercourse, with straining during a bowel

movement, and while removing a tampon.

Progestogen-only

vaginal rings are also available in certain

countries, with different durations of action. They act through their

progestational effects on the cervical mucous and endometrium, as for other

progestogen contraceptives. Progering (Andromaco Laboratories, Chile) is a

brand suitable to extend the contraceptive effectiveness of lactation in

breastfeeding women. It was initially tested for 3 months (16), but a more recent study showed that it is

effective for 4 months without affecting breast-feeding or the rate of infant

growth. It also prolonged the period of lacational amenorrhoea (17). The ring can be removed for comfort during sexual

intercourse, but additional contraception will be necessary for one week if it

has been removed for more than 3 hours. Bleeding disturbances are common, as

for other progestogen only contraceptives.

Efficacy of hormonal contraceptive

The statistics used to

compare the efficacy of different contraceptive methods is usually documented

as failure per hundred women years. This estimate of efficacy refers to the

first year of use, though the longer a woman uses a contraceptive method, it is

less likely for that method to fail. It is important to understand that failure

rate depends on many factors which can reduce the efficacy of the contraceptive

method. Parts of these factors are related to the method itself, but a major

part is related to the way it has been used. This is reflected by failure in

relation to the typical use and perfect use of the specific contraceptive.

Perfect use is a measure of efficacy when the method has been used perfectly

according to the manufacturer’s guidelines, without fail. Failure in such cases

reflects the inherent capabilities of the method itself. On the other hand,

typical use failure rate reflects the probability of pregnancy during the first

year, allowing for non-compliance and incorrect use of the method. This is the

statistics usually quoted in the literature, which is obviously affected by

many confounders. It is understable why long acting contraceptive methods which

rely less on patients’ compliance offer similar typical and perfect use failure

rates. The perfect use failure rates of depoprovera and Norplant are 0.03% and 0.05%

respectively, with the typical use failure rates being almost identical. This

is in contrast to the other methods which depend on the patients’ compliance.

The combined oral contraceptive pills perfect use failure rate is approximately

0.1-0.5%, but the typical failure rate is as high as 5%

(18).

Non

contraceptive uses of hormonal contraceptives

Family planning remains to be the most common

indication for using hormonal contraceptives. Nonetheless, patients who need

such protection may have other gynaecological or chronic medical problems,

which make proper selection of a specific brand with a specific route of

administration more important. These issues will be discussed in the following

sections of this chapter.

2. Cycle control in

oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea is an indication to prevent

endometrial hyperplasia and hypo-oestrogenic state. This should be done after

making a proper diagnosis of the initial cause of anovulation. This is

especially so for thyroid dysfunction and hyperprolactinaemia, as treatment of

these conditions is most likely to correct the menstrual problem.

Oligomenorrhoeic and amenorrhoeic women with polycystic ovary syndrome are at

risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia. This increases the risk of

endometrial carcinoma. Using an oral contraceptive pill

to induce regular monthly withdrawal bleeding will reduce this risk.

Alternatively, a mirena system can be used instead. On the other hand, young

women with hypo or hyper gonadotrophic hypogonadism are at risk of developing

hypoestrogenic side effects including osteoporosis. One option to deal with this

problem is to use a low dose oral contraceptive brand.

3. Treatment of

abnormal uterine bleeding especially excessive blood loss is also an indication

for using an oral contraceptive pill, or the mirena system. This is especially so in

patients with dysfunctional uterine, when no specific treatable endocrine or

organic uterine causes can be detected. This subject has been discussed in

detail before in this chapter under the subtitle ‘Intrauterine contraceptive

devices’.

4. Treatment of

hyperandrogenisation is an important indication for using non androgenic oral

contraceptive pills. This is affected by inhibiting ovulation, reducing ovarian

androgens production, and increasing the level of SHBG which reduces the level

of free testosterone. It is also important to exclude other specific treatable

conditions which may increase the level of serum androgens, including ovarian

and adrenal tumours. Adult onset adrenal hyperplasia should also be excluded,

as treatment usually entails suppression of the adrenal androgens as a

priority. The highest level of SHBG is reported after using a combined pill

with cyproterone acetate as the progestogen fraction (Dianette, Bayer

plc). The role of

non androgenic progestogens has already been discussed in this chapter. Pills

with low progestogen / oestrogen activity are preferable in the treatment of

patient with acne, but may not give the best cycle control, and breakthrough

bleeding is more likely. The direct antiandrogenic effect of drospirenone in reducing 5a reductase

activity is well utilised in the combined pill Yasmin (Bayer plc).

5. Using an oral

contraceptive pill to inhibit ovulation has been shown to reduce the risk of

developing functional ovarian cysts while under treatment (19). This effect has been well documented

for high dose older contraceptives with 50 µg ethinyl oestradiol, but not for

the lower dosage group. Once a cyst was formed such treatment achieved similar

results to expectant management (20, 21). A

significant similar effect has also been found with other benign ovarian tumours including serous and mucinous adenomas, teratomas

and endometriomas (22). The reduction in risk

was related to the duration of use. Similar to functional cysts, oral

contraceptives are not useful for the treatment of these benign ovarian cysts

once they already developed.

6. Oral

contraceptive pills are also used in cycle preparation during assisted

reproduction treatment cycles. This is done usually in cases with irregular

menstruation for good planning of the treatment cycles. One protocol involves

the use of an oral contraceptive pill after a progestogen withdrawal bleeding episode. This is followed by daily injections

of a gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist, from day 17 of the cycle

to affect down regulation of the pituitary gland. Nasal sprays can be used

instead. Controlled hyperstimulation is started within a day or two after the

withdrawal bleeding has started, usually within a week after stopping the pill.

There will be less risk of developing an ovarian cyst following the GnRH

agonist during such a protocol. Accordingly, a similar protocol can be

prescribed for patients who developed ovarian cysts following GnRH agonist use

during previous assisted reproduction treatment cycles.

7. The use of

oestrogens and combined oral contraceptive pills in the management of young

women with absent or delayed pubertal development has been discussed in Chapter

2. Unopposed oestrogen is usually a priority for some time till normal height

has been attained, before converting to an oral contraceptive pill.

8. Low dose combined

contraceptive pills can also be used as hormone replacement therapy in cases of premature ovarian failure as

discussed in Chapter 10. These patients usually need a higher oestrogen dose

than women who went through natural menopause. Furthermore, having regular

withdrawal bleeding has a good psychological effect on these patients. Neither

the combined contraceptive pills nor any designated hormone replacement therapy

are effective as contraceptives in these cases. Pregnancies have been reported

in young women with premature ovarian failure while on the pill. This

information should be conveyed to all patients in such a situation who are

adamantly keen not to get pregnant. Women with anorexia nervosa are at special risk of severe hypoestrogenism.

Using a low dose combined contraceptive pill will provide the missing

oestrogen, while the patient is having the necessary psychological treatment.

This is also valid for professional women athletes, who are at risk of the

triad of amenorrhoea, anorexia and osteoporosis.

9. Medical treatment of endometriosis also involves using different types of

hormonal contraceptives. Cyclic or continuous use of oral contraceptive pills

are two options. Recently, the extended use of an oral contraceptive pill for

84 days has been introduced. Depoprovera and the mirena system are also useful in this respect. The dominant

progestational effect of all these drugs is the main factor in controlling

endometriosis growth and symptoms. This does not give permanent cure, and

symptoms and signs usually recur after medication is suspended. Furthermore,

such medication is not suitable for women who are keen to conceive, which is a

real limitation for this therapy.

10. The role of

hormonal contraceptives in the management of premenstrual dysphoric disorders

has been discussed in Chapter 10. Suffice to say that mixed results have been

reported about the effect of the oral contraceptive pill, and the risk of

worsening symptoms during the pill free period. This resulted in the release of

brands with 24 and 26 pills to reduce the pill free period. Using an extended

brand for 84 days, like Seasonale (Duramed Pharmaceutical, Inc), has also been

shown to improve premenstrual dysphoric disorders. It contains 84 active pills,

each containing 30 µg ethinyl oestradiol and 0.15 mg levonorgestrel, with 7

inert tables. A pill which gained notoriety in this respect is Yasmin (Bayer

plc), as the

progestogen fraction has been replaced with drospirenone which is a

spironolactone derivative. Each pill contains 30 µg ethinyl

oestradiol and 3 mg drospirenone, and used for 21 days with one pill-free week.

Another pill with 20 µg ethinyl oestradiol and 3 mg drospirenone with 24 active

pills is marketed in America, and used especially for premenstrual dysphoric

disorders. In very severe cases, the mirena system can be used, together with continuous

transdermal oestrogen.

11. The mirena system has a wide range of non contraceptive benefits

which have been alluded to before in this chapter. One benefit not mentioned

before, is its role in protecting the endometrium against the chronic

hyperplastic effect of tamoxifen during treatment of breast cancer. Other

benefits include control of endometriosis induced pelvic pain, and for endometrial

protection in postmenopausal women on continuous oestrogen replacement therapy. An extra important benefit of the mirena system is

its effect in reducing the symptoms and size of endometriotic lesions in the

rectovaginal septum (23). This will obviate the

need for the difficult surgery necessary to deal with this pathology in most

cases. Furthermore, suggestions have been put forward to use it immediately

after endometriosis surgery to reduce the need for further operations in the

future (24). Levonorgestrel has been found in

the peritoneal fluid in significant amounts, approximately two thirds of the

serum level, in women who showed improvement in their symptoms after six months

of using a mirena (25). Similarly, the level of

the serum marker CA-125 showed equivalent decline after long term use of the

device as for GnRH-a, when used for the treatment of endometriosis (26). All these effects were related to the high levels

of peritoneal levonorgestrel causing increased programmed cell death

(apoptosis), atrophy of the ectopic endometrial glands, and decidual

transformation of the stroma. It has also been reported to have

anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects (27).

Furthermore, levonorgestrel has been shown to decrease and then block DNA

synthesis and mitotic activity (28).

Other coincidental benefits of hormonal

contraceptives

There are

many coincidental health benefits related to the use of the oral contraceptive

pills including:

• An epidemiological study reported by Schlesselman in 1991 (29) showed a

duration-related protective effect of combined oral contraceptive pills against

endometrial cancer. The risk before

the age of 60 years was reduced by about 38% with two years of use. Longer use

for 4, 8, and 12 years, conferred 51%, 64%, and 70% reduction in endometrial

cancer risk respectively. Such protective effect lasted for ≥15 years after

stopping medication.

• Many reports documented a protective effect of oral contraceptives

against ovarian cancer in general. This risk also decreased with increased

duration of use. The adjusted odd ratio for ovarian cancer with any past use of

oral contraceptives was 0.5 (95 CI 0.3 – 0.8). A 60% risk reduction was noted

after 6 years of use or more (30). Such

protective effect was noted even in carriers of BRCA1 (odd ratio, 0.5; CI 0.3 –

0.9), and BRCA2 mutations (odd ratio , 0.4; CI 0.2 – 1.1)

• Reduced risk of functional ovarian cysts is another benefit related to

suppression of ovulation. Risk reduction was also related to the duration the

oral contraceptives use. Such benefit persisted for at least 15 years after

stopping using the pill. The protection rate in comparison to non-users has

been estimated as 30% for women who used the pill for 4 years or less. This

figure increased to 50% and 80% for 5 – 11 years, and >12 years of the pill

use respectively (31, 32).

• Reduced risk of colorectal cancer has been documented for patients

who used oral contraceptives with 50 µg ethinyl oestradiol, with a relative

risk of 0.6 after 96 months of use. The effect of low dose brands has not been

verified.

• Decreased incidence of benign breast diseases including fibrocystic

changes and fibroadenomas has been attributed to the use of oral combined

contraceptives. This effect was seen even after only one or two years of use (33), and lasted for one year after stopping the pill (34). Conversely, the ESHRE Capri Workshop Group in 2005 (35) thought there

were significant problems with bias, study design and interpretation of results

related to this topic. Furthermore, they thought there was no evidence of

biological plausibility. In short, they did not endorse the idea of a

beneficial effect on the breasts.

• The subject relating bone mass density to hormonal contraception has

generated a lot of contradictory results. The osteoporotic effect of

depoprovera has been discussed already. Oral

progestogens only pills do not inhibit ovarian function, and do not have

similar effect on bone density. The difficulty with studies which addressed

bone mass density has been confounded by different factors which affect bone.

Examples of such factors included hereditary factors, age, body mass index,

smoking, level of physical exercise and diet. On the other hand, there is some

evidence of a little favourable effect of the combined oral contraceptives on

bone mineral density and fracture risk in women of reproductive age as

concluded by the ESHRE Capri Workshop Group (35).

This is despite of the fact that oestrogen blood concentrations over the whole

month are lower in women using the combined oral contraceptive pill than during

natural ovulatory cycles. They did not endorse any benefit on bone mass density

in patients with anorexia nervosa.

Use of

hormonal contraceptives by women with known medical problems

Young women with different non gynaecological medical

problems may need contraceptive advice to prevent unplanned or unwanted

pregnancies. This occasionally creates different difficulties, because of the

direct effect of the method used on the medical condition, or its interaction

with the different drugs necessary to control her basic medical problem. The

most likely conditions to be encountered in this age group include obesity,

high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, migraine, hypothyroidism, pituitary

adenomas and thrombophilias. Patients with certain risk factors may also

request contraceptive advice. This group includes women with previous history

of deep vein thrombosis, and those with personal or family history of breast

cancer

Obesity

It is not uncommon for obese patients to seek

contraceptive advice. They may even have pre perceived ideas against using

barrier methods for different reasons. A more urgent situation can arise when

an obese patient presents with irregular or excessive menstrual blood loss,

which needs immediate hormonal treatment and cycle control in the long term.

Obesity is a known risk factor for venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism,

insulin resistance, and diabetes mellitus. There is

increased risk of thromboembolism in women with BMI >35 kg/m2.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists considered a BMI of 40

kg/m2 or more as a contraindication to use oral contraceptives. In

fact the risks of using oral contraceptives generally outweigh their benefits

for women with BMI of 35 to 39 kg/m2. This is coupled with a

negative correlation between BMI and the contraception effectiveness of

transdermal patches and the vaginal ring, leading to higher failure rates. This

may be due to altered steroid metabolism, and / or dilution of the steroid dose

in a larger blood volume. The evidence for an association between oral

contraceptives failure and obesity has been conflicting. This subject has been

reviewed by Brunner et al in 2006 (36). They

confirmed a negative association, but the results were largely attenuated after

adjustments for age, ethnicity and parity. Taking all the risks involved into

consideration, it seems that the preferred option for obese women is a mirena

system. The revised

Depoprovera Product Monograph in 2006 (3)

reported variable results related to weight gain after using the product. The

majority of studies reviewed showed weight gain of 5.4 lbs (2.5 kg) at the end

of one year. Other studies reported weight gain of 8 lb (3.5 kg) by the end of

the second year, but 20-40% of depoprovera users actually lost weight during treatment.

High

blood pressure

High blood pressure is another possibility in

patients seeking contraceptive advice. It is a risk factor for cardiovascular

events and stroke, even in young women, who are normally expected to have a low

risk (37). The estimated annual

incidence of myocardial infarction and strokes has been reported as 1.7 and

34.1 cases per 1 million respectively, for normotensive women aged 30–34 years.

These rates increased to 10.2 for myocardial infarction and 185.3 for stroke

among hypertensive women of the same age group (38). Women using combined oral contraceptives are at increased

risk of developing high blood pressure. Certain factors are known to increase

this risk, including a strong family history of high blood pressure especially in female relatives, and history of high blood

pressure during a previous pregnancy. Other risk

factors include racial origin, age, obesity, smoking and alcohol abuse. Duration of the oral contraceptives use is also

important. There were higher age-adjusted blood pressure levels after 8 years

of use than in women who used the pill for shorter periods of time as reported by

Lubianca et al in 2003 (39). The same authors concluded that hypertensive women

on oral contraceptives had significant elevation of diastolic blood pressure

and poor blood pressure control, independent of age, weight and

antihypertensive drug treatment. In a subsequent publication Lubianca et al in

2005 (40) reported reductions of 15.1+/-2.6 mm Hg and 10.4+/-1.8 in systolic and

diastolic blood pressure respectively after stopping oral contraceptives use.

They recommended stopping such medication as an effective antihypertensive

intervention in such a clinical setting. This finding was agreeable with another

study reported by Atthobari et al in 2007 (41) who

showed worsening of high blood pressure with hormonal contraceptives and its

improvement after discontinuation of medication. It also showed some

deterioration in renal function during usage of hormonal contraceptives. Urine albumin excretion increased

by 14.2% in starters (P = 0.074), and fell by 10.6% after stopping

medication (P = 0.021). On the other hand, the glomerular filteration

rate fell by 6.3% in starters (P < 0.001), and did not recover after

stopping the contraceptive. The same authors reviewed previous studies for the

correlation between hormonal contraception and renal function, in relation to

these findings. Two previous studies proposed that contraceptives use may be

associated with an increased risk of microalbuminuria, independent of the blood

pressure effect. On one hand, higher levels of albuminuria are considered as an

early marker of vascular endothelial damage, but there is no significant

evidence relating renal disease to the use of hormonal contraception. Both

pathologies are related to an increased risk of progressive renal failure and

excess cardiovascular morbidity and mortality (41).

This

section can be concluded that the combined oral contraceptive pill is better

avoided by hypertensive patients, and by women liable to develop high blood

pressure. Progestogen only contraceptives can be used instead. Nonetheless,

controlled mild high blood pressure as an isolated problem is not an absolute

contraindication against using a low dose oral contraceptive pill. Readjustment

of the antihypertensive treatment dose may be necessary, due to stimulation of

the renin angiotensin system and aldosterone production by oestrogens. At

the same time, regular medical supervision will be needed, if the patient opted

to continue with the same medication, rather than using an alternative method.

Conversely, uncontrolled or complicated hypertension is an absolute

contraindication to use the combined oral contraceptive pill. Other risk

factors like obesity and smoking should be taken into consideration when making

the decision.

Thrombophilia

and history of thromboembolism

Thrombophilia is a term used to indicate increased

tendency to intravascular coagulation. It may follow hereditary or acquired

causes. Congenital factors include factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin, protein C and S, and

antithrombin III deficiencies. High homocysteine and sickle cell disease are

other factors to consider. Thombophilia can also be acquired due to

antiphospholipid antibodies. Factor V Leiden forms the most common inherited

thombophilia, and 3 – 8% of

Caucasians carry a copy of the mutation in each cell. Furthermore, 1 in 5000

individuals carries 2 copies of the mutation. The risk of thromboembolism for

Factor V Leiden is >10 times more (80%) in this group than for the

heterozygous state (7%). It is less common in other ethnic groups. It is

important to note that not all thrombophilias carry the same risk of venous

thromboembolism. The lowest risk is attributed to a single mutation such as

Factor V Leiden, and the highest to antithrombin deficiency (42). Using the combined oral contraceptive pills is

associated with a small increase in thrombosis and pulmonary embolism risks. In

numerical terms, about 20 – 30 women in every 100,000 pill users may develop

deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Previous history of either problem

or a personal history of thrombophilia will increase the risk. Despite the

controversy regarding the increased risk with third compared to second

generation oral contraceptives, epidemiological data confirmed this increased

tendency for venous, but not arterial thrombosis (43).

Furthermore, the increased risk of venous thromboembolism is more pronounced

during the first year of use. Other contributing factors included obesity,

cigarette smoking, immobility, fractures, surgery and cancerous conditions

especially of the pancreas. There is an exponential increased risk when genetic

factors are combined with these conditions. Accordingly, great care should be

taken to identify patients with such genetic risk factors, but screening all

women is not indicated before prescribing oral or other hormonal

contraceptives. Additionally, oestrogen containing pills should be avoided in

these cases when contraception is needed. Though progestogen contraceptives,

whether oral or injectable, do not increase the thrombosis tendency in the

general female population, their role in individual women with thrombophilia

has not been investigated. Accordingly, there is an opinion that a

copper IUCD should be the first-line contraceptive method for women with a

history of deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or coronary events (44).

Diabetes

mellitus

Classical teaching has always associated

combined oral contraceptives, and in some cases even the progestogen only

brands, with changes in carbohydrate metabolism. Such changes included

decreased glucose tolerance and increased insulin resistance, which are risk factors

for type II diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. This issue has been

addressed by a meta-analysis published by Lopez et al in 2009 (45). They concluded

that the current evidence showed a limited effect for hormonal contraceptives

on carbohydrate metabolism in women without diabetes. Furthermore, they

criticised many of the published articles because of the small numbers of women

involved, lack of comparison between different types of contraceptives, and

lack of information regarding the effects among overweight women. In the same

year, Cagnacci

et al (46) found that vaginal contraceptive

rings were less likely to change insulin resistance than combined oral

contraceptives. They concluded that a vaginal ring may be a better choice for

long-term contraception in women at risk for developing diabetes mellitus or

the metabolic syndrome. In a study which addressed the effect of depoprovera injections, Xiang et al found increased risk

of diabetes which they explained by three factors (47):

- The drug was used by women with increased

baseline diabetic risk;

- There was associated weight gain during

medication;

- The drug was used in cases with high baseline

triglycerides and/or during breast-feeding.

All this information

indicates that proper selection of the suitable contraceptive should always

take into consideration the inherent characteristics of the drug to be used,

and the risk factors shown by each individual woman.

Contraception is an

important issue for diabetic women, as unplanned pregnancy can induce major

maternal and perinatal complications. There was little evidence that changes in

blood sugar control induced by combined oral contraceptives had any clinical

consequence as reported by Shawe and Lawrenson 2003 (48). Furthermore, low

dose combined contraceptive pills have minimal effect on the lipid profile

which may even by beneficial. Conversely, there is some concern regarding the

effect of oral and injectable progestogens on HDL and LDL cholesterol levels. Diabetes mellitus

is a risk factor for thromboembolism and cardiovascular diseases, but well

controlled diabetes is not an absolute contraindication for using the oral

contraceptive pill. The same authors (48) stated

that short term studies of young women with uncomplicated

diabetes who were taking low-dose combined oral contraceptives have been

reassuring. On the other hand, patients with complicated diabetes and

macrovascular or microvascular changes should be prescribed nonhormonal

contraceptive methods. The same is valid for cases with uncontrolled diabetes, or

in the presence of other risk factors like obesity, hypertension or smoking. In

a different approach Nikolov et al in 2005 (49) made a clear

distinction between types I and II diabetics in relation to contraceptive

advice. They recommended the use of low dose

combined contraceptive pills in women with uncomplicated type I diabetes of

less than 15 years duration. A change in the insulin dose and control of body

weight will be needed to maintain good glycaemic control. Conversely, they

advised against using combined oral contraceptives in women with type II

diabetes, because they may provoke clinical changes and

worsen the progress of the disease itself. This last point is very much valid

for prediabetics and diabetics controlled only by diet. Further deterioration

of the glycaemic condition, which may follow using combined contraceptives,

adds a further burden on the patient to take hypoglycaemic drugs, which also

adds cost and the need for more strict compliance.

Complications

and risks of hormonal contraceptives

This section will be dealt with in

bullets form to focus the attention of the reader, as most points have already

been addressed before in this chapter. Few of the complications are

gynaecological in nature, but systemic and organ specific complications or

risks will also be addressed.

- Dysfunctional

uterine bleeding may follow inappropriate or prolonged use of oral

contraceptives. This is also valid for progestogen only contraceptives

whether oral, injectable or implants. It is not unusual for dysfunctional

uterine bleeding following depoprovera to be unresponsive to treatment with

oestrogen or tranexamic acid. Use of further progestogens either as norethisterone

or medroxyprogesterone acetate may even increase the bleeding problem.

- Long term

amenorrhoea and delayed return of fertility potential can follow

depoprovera injections. Though 9 months after the

last dose was a figure usually quoted for return of fertility, many women

do not menstruate for much longer periods of time.

- There is

increased risk of thromboembolism in obese patients and smokers and in

women >35 years of age, especially with the combined contraceptives as

discussed before.

- Osteoporosis

with long term injectable progestogens is a risk factor. It can be more

significant in very lean young teenage girls as the maximum bone density is usually attained by the age of 20

years.

· Unfavourable

changes in cervical cytology have been seen in women using combined oral

contraceptive pills. Furthermore, prolonged use of these pills has been

associated with a small increased risk of cervical cancer. Among current users

of the pill, the relative risk (RR) after 5 years of use was 1.9 (95% CI,

1.69-2.13) compared to those who never used the pill. There was gradual decline

in the risk, which returned to normal 10 years after stopping the pill. This

pattern was seen in invasive and in situ cancers and for women who tested

positive for the high risk human papilloma virus, as reported by the

International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer in

2007 (50). The

same group estimated an increased cumulative incidence of cervical cancer from

3.8 to 4.5 per 1000 women by the age of 50 years in women who used the pill for

10 years between the ages of 20 and 30 years, in developed countries. The

corresponding increase was from 7.3 to 8.3 per 1000 for developing countries.

The reason for this increased risk of cervical cancer was not well elucidated,

but was thought to be an association rather than a cause and effect

relationship. Women using the pill are more likely to be sexually active and

may not use barrier contraceptive means regularly. This can put them at

increased risk of contacting human papilloma virus, which is the likely cause

of cervical cancer. Accordingly, it is important that all women on combined

oral contraceptive pills should have regular cervical smear screening,

especially if human papilloma virus infection was detected (51). A note should be documented here about the effect

of depoprovera. An overall non

significant relative risk of 1.11 (95% CI, 0.96 – 1.29) has been reported for

invasive sqaumous cell cervical carcinoma in women who ever used the drug. This

was not affected by the duration of use, or the times since the initial or most

recent injection (2).

· The issue

relating breast cancer risk to the oral contraceptive pill is more complicated

than the pill’s relationship to cervical cancer. It is a subject which had

attracted, and still attracts the attention of the media and public. Many

scares have hit the public in waves since the 1970s, which lead to thousands if

not millions of unplanned or unwanted pregnancies, and equally distressing

terminations of pregnancies. The relationship has been confounded by the

multifactorial nature of breast cancer, which is affected by many variables. The odd ratio is 200 for those

with the BRAC gene mutation. A figure of 3 has been reported for women with

familial history of breast cancer (52).

Furthermore, many life style and other related variables have been known to

increase the risk. The list includes lack of exercise, excessive alcohol

intake, cigarette smoking, postmenopausal obesity, early menarche, late

menopause, first full-term pregnancy after the age of 35 years, and reduced

breast feeding (53). Each of these factors increased the risk

of breast cancer more than the risks reported for combined oral

contraceptives (53). As an example of such

confounders, women who had their menarche before the age of 12 years had 30%

higher risk of developing breast cancer than those who started menstruating by

the age of 15 years, as reported by ESHRE Working Capri Group (35). A meta-analysis

published by Kahlenborn et al in 2006 (54) examined 34 studies that met stringent inclusion

criteria since 1980, for an association between using oral contraceptives and

premenopausal breast cancer in general. A small increased risk with an odd

ratio (OR) of 1.19 was found (95% CI, 1.09-1.29). Both parous (OR, 1.29; 95%

CI, 1.20-1.40) and nulliparous (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.92-1.67) women were

affected. Prolonged use did not change the OR risk for nulliparous women. The

risk was stronger when the pill was used before the first full term pregnancy.

Furthermore, the maximum risk was seen when the pill was used 4 years before

the first full term pregnancy, with an OR of 1.52 (95% CI; 1.26-1.82). Despite

all these figures, the risk of breast cancer remains to be small, and the

benefits of using the oral contraceptive pill outweigh their risks in most

women. To put this statement into mathematical perspective, there will be 0.5

additional breast cancers per 100,000 women 16-19 years of age, during the time

of use and 10 years follow up. The corresponding figures for women in the age

groups 20-24 years and 25-30 years are 1.5 and 4.7 additional cancers per

100,000 respectively as reported by Reid in 2007 (53).

Emergency

contraception

Emergency or postcoital contraception

should be used to prevent unwanted pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. It

is an occasional method and should not be used as a regular means of

contraception. Copper intrauterine contraceptive devices are the most efficient

means if inserted within 5 days of unprotected intercourse, with a failure rate

<1.0% (55). They act mainly by preventing

fertilisation through the toxic effect of copper on sperm, but impede

implantation at the same time. TT380 Slimline (Durbin PLC, South Harrow, Middlesex, UK) and

T-Safe 380A (Williams Medical Supplies Ltd, Rhymney,

Gwent, UK) are the most effective, and have the lowest failure rate. They are

the preferred method for women using liver enzymes inducing drugs, such as

barbiturates, carbamazine, rifampicin and phenytoin. Nulliparous women could be

offered the Mini TT380 Slimline, which has a small plastic frame.

The two main hormonal means are Levonorgestrel

1500 µg tablets and ulipristal acetate which is a synthetic second generation

selective progesterone receptor modulator. The levonorgestrel contraceptive

pill (Levonelle 1500, Bayer Schering)

is licensed for use within 72 hours of intercourse. It prevents pregnancies in

95%, 85% and 58% of the cases if used within 24, 24 – 48 and 48 – 72 hours

after the first intercourse respectively (56).

It interferes with follicular development and impairs ovulation, with little

evidence regarding inhibition of implantation. Another tablet should be taken

if vomiting occurs within 3 hours after taking the pill. It is also recommended

that a woman on liver inducing enzymes should take 2 tablets soon after

unprotected intercourse, if she is not agreeable to use a copper IUCD. Ulipristal

acetate (30 mg tablet) could be used up to 120 hours

after intercourse, and is more effective than levonorgestrel for inhibiting

ovulation (57, 58).

It also affects implantation, and accordingly could be used for emergency

contraception after ovulation but before the expected time of implantation. No

teratogenic effects have been attributed to either drug, and termination of

pregnancy is not indicated on this context in cases of failed contraception. Both

drugs could lead to menstrual irregularities and delay of menstruation, which

may cause patients some concern.

An alternative method of emergency hormonal

contraception is to take 4 combined oral contraceptive pills immediately after

intercourse and repeat the dose 12 hours later. Microgynon 30 (Bayer Schering)

has been recommended for this purpose (59). This

may lead to nausea and vomiting, and an anti-emetic drug may be needed in these

cases. This method is indicated if the single-tablet protocols or copper IUCD

are not available or unacceptable.

Perimenopausal

contraception

Previous studies showed lower tendency by

women over the age of 40 years to use contraception, with 40% opting for

sterilization in the United Kingdom (60). This

pattern may change because of the introduction of newer methods of

contraception. It is important to emphasise that no method of contraception is

contraindicated on the basis of age only, in the absence of risk factors or

medical problems. Perimenopausal women are more likely to develop high blood

pressure, diabetes mellitus, obesity and dysfunctional uterine bleeding which

make selection of an appropriate contraceptive method rather difficult. At the

same time, pregnancy at this age carries great risks for the mother and fetus,

and appropriate contraception should be guaranteed to prevent unplanned

pregnancies. The following points should be taken into consideration when

offering contraceptive advice to women in this age group:

·

It is most important to take a woman’s preference into

consideration and to discuss with her the merits and drawbacks of her chosen

method of contraception to improve compliance. Certain taboos may be attached

to the use of certain methods which make them less acceptable in different

areas and cultures.

·

Women above the age of 40 years can use combined hormonal

contraceptives up to the age of 50 years, unless there are coexisting risk

factors. They should be switched to another form by that age. The last

statement is also valid for women using injectable progestogen only

contraceptives, but inherent predisposition to osteoporosis should be taken

into consideration even in younger women.

·

Smoking is a significant cardiovascular risk factor even

at the age of 35 years and in younger obese women. This risk falls

significantly one year after stopping smoking and almost disappears 3-4 years

later.

·

There is 50% increased risk of thromboembolic attacks

among cigarette smokers independent of oral contraceptives use or age (61).

·

Women with migraine, history of stroke or cardiovascular

disease should not be prescribed combined hormonal contraceptives.

· The progestogen only pill and mirena system are good

options, but there is a higher risk of dysfunctional uterine bleeding with the

former method, which made it unsuitable for many perimenopausal women (62). They are not associated with increased risk of

thromboembolism (61, 63). Both methods can be

used by patients with previous history of ischaemic heart disease and stroke,

but the progestogen only pill should not be used during an active thrombotic

episode. The risks involved by using injectable progestogen only contraceptives

outweigh their benefits in these conditions. The role of copper IUCD in such

cases has already been mentioned before (44).

· Monophasic contraceptive pills with £30 µg ethinyl

oestradiol and low dose northisterone or levonorgestrel are good first line

options for women with no risk factors who opted to use a combined pill. The

risk of venous thrombosis decreases with lower oestrogen dose and duration of

use.

· The non-contraceptive health benefits of low dose

contraceptive pills alluded to before, justify their use in healthy

perimenopausal women (63). Kaunitz viewed their

use in this age group as a general strategy not only to provide effective

contraception, but also to improve perimenopausal symptoms and to enhance

quality of life (64).

· Oral contraceptive pills with desogestrel, gestodene or

drospirenone have significantly higher risk of venous thrombosis than other

brands containing levonorgestrel, as confirmed by Lidegaard et al in 2009 (65).

· In general, the risk of cerebral thromboembolic attacks is

reduced by >30% when using low dose pills compared to 50 µg preparations (61). This is equivalent to one additional death per

one million low dose pill users per year in comparison to IUCD users (66). On the other hand the General Practice Research

Study (67), and the WHO Collaborative Studies of

Cardiovascular Disease and Steroid Hormone Contraception (68, 69) showed no

increase in mortality rate from stroke or venous thrombosis in low dose pill

users.

· A copper IUCD is an alternative non-hormonal method of

contraception, but may exacerbate menstrual problems in this age group (70). The T380 device offered contraceptive

effectiveness equivalent to surgical sterilization (71).

Accordingly, such a device may be offered to women free of any pre-existing

menstrual problems, otherwise the mirena system should be used if this mode of

contraception is preferred (72).

· Combined HRT does not provide effective contraception and

women on such medication should use effective contraception till the age of 55

years. This can be provided by the progestogen only pills or a mirena system.

Two FSH blood level estimations will be needed 6 weeks after stopping HRT for

confirmation of the menopause, before contraception can be stopped (73).

Summary

The subject of hormonal contraception has

been a prime issue in the public domain many times over the last 30 years, but

mostly for the wrong reasons. Women who seek contraceptive advice are mostly

young and healthy, and can use hormonal contraceptives safely in the majority

of cases. This is a different scenario to other patients who have known risk factors,

or are currently under treatment for one or another chronic illness. An

unwanted pregnancy can cause more damage than the small risks of inducing

cardiovascular problems or breast cancer, which are not very common in this

young age group. Furthermore, the thromboembolic risks of pregnancy exceed

those related to the use of the combined oral contraceptive pill. The medical

and psychological risks involved with termination of pregnancy should be taken

into consideration as well. Many women can not even consider the option of

having a termination, because of ethical or religious reasons, and get stuck

with an unwanted pregnancy. Accordingly, the most appropriate contraceptive

should be selected for each individual woman taking into account her own preferences,

any available risk factors, the issues of expenses, compliance, and ease to see

a medical or nursing professional when necessary. The other non contraceptive

benefits mentioned before in this chapter should be added to the whole package

when discussing the issues related to contraception with patients.

References

1. Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Poindexter AN III, Bateman L, Reid ED.

Experiences of injectable contraceptive users in an urban setting. Obstet

Gynecol. 1996; 88: 227 - 233.

2. Product

Monograph. Depoprovera. Pfizer Canada Inc 2006.

3. Pettiti DB, Piaggio G, Mehta

S, Cavioto MC, Meirik O. Steroid hormone contraception and bone mineral

density: a cross-sectional study in an international population: the WHO Study

of Hormonal Contraception and Bone Health. Obstet Gynecol. 2000; 95: 736 - 744.

4. Westhoff C, Britton JA, Gammon

MD, Wright T and Kelsey JL (2000) Oral contraceptives and benign ovarian

tumours. Am J Epidemiol 2000; 152: 242 – 246.

5. Long-acting

hormonal contraceptives. In: FIGO Manual of Human Reproduction, Vol 2. Fathalla

MF, Rosenfield A and Indriso C (ed). The Parthenon Publishing Group. Casterton

Hall, 1989; 67 – 83.

6. Bahamonds

L, Lavin P, Ojeda G, Petta C, Diaz J, Maradiegue E, Monteiro I. Return of

fertility after discontinuation of the once a month injectable contraceptive,

Cyclofem. Contraception 1997; 55: 307 - 310.

7. Gallo MF, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF, d'Arcangues C. Combination

injectable contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. Art No:

CD004568. DOI: 10.1002/14651858. CD004568.pub3.

8. Rai

K, Gupta S, Cotter S. Experience with Implanon in a northeast London family

planning clinic. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2004; 9: 39–46.

9.

Creasy

GW, Abrams LS, Fisher AC. Transdermal Contraception. Semin Reprod Med 2001;

19(4): 373 - 380.

10. Smallwood GH, Meador ML, Lenihan JP, Shangold

GA, Fisher AC, Creasy GW; Ortho Evra/Evra 002 Study Group Efficacy and safety

of a transdermal contraceptive system. Obstet Gynecol 2001; 98: 799 - 805.

11.Archer DF, Bigrigg, Smallwood GH.

Assessment of compliance with a contraceptive patch (Ortho Evra TM/Evra TM)

among North American women. Fertil Steril 2002; 77: S27 - S31

12. Lahteenmaki P, Rauramo I, Backman T.

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system in contraception. Steroids 2000; 65: 693

- 697.

13. Fong YF and Singh K. Effect of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine

system on uterine myomas in a renal transplant patient. Contraception 1999; 60

(1): 51 - 53.

14.Magalhaes J, Aldrighi JM and de Lima GR.

Uterine volume and menstrual patterns in users of levonorgestrel-releasing

intrauterine system with idiopathic menorrhagia or menorrhagia due to

leiomyomas. Contraception 2007; 75 (3): 193 - 198.

15. Roumen FJME, Apter D, Mulders TMT,

Dieben TOM. Efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of a novel contraceptive

vaginal ring releasing etonogestrel and ethinyl oestradiol. Human Reprod 2001;

16:469 - 475.

16. Massai R, Miranda P, Valdẻs P, Lavin P,

Zepeda A, Casado ME, Silva MA, Fetis G, Bravo C, Chandia O, Peralta O, Croxatto

HB and Diaz S. Preregistration study on the safety and contraceptive efficacy

of a progesterone-releasing vaginal ring in Chilean nursing women.

Contraception 1999; 60(1): 9-14.

17. Massai R.

Quinteros E, Reyes MV, Caviedes R, Zepeda A, Montero JC, and Croxatto HB.

Extended use of a progesterone-releasing vaginal ring in nursing women: a phase

II clinical trial. Contraception 2005; 72(5): 352 – 357.

18. Contraceptive

Technology. Robert A Hatcher (ed); 17th Revised Edition, 1998;

Ardent Media Incorporated, page 410.

19. Holt VL,

Daling JR, McKnight B, Moore D, Stergachis A and Weiss NS. (1992) Functional

ovarian cysts in relation to the use of monophasic and triphasic oral

contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol 1992; 79: 529 – 533.

20. Turan C, Zorlu CG, Ugur M, Ozcan T, Kaleli B and Gökmen O. Expectant

management of functional ovarian cysts: an alternative to hormonal therapy. Int

J Gynaecol Obstet 1994; 47 (3): 257 - 260.

21. Nezhat FR, Nezhat CH, Borhan S and Nezhat CR. Is hormonal suppression

efficacious in treating functional ovarian cysts? J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc

1994; 1 (4, part 2): S26.

22. Westhoff C. Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception.

Metabolic parameters and mood changes. J Reprod Med. 1996; 41 (suppl 5): 401 -

406.

23. Spencer JE. Anovulation and monophonic cycles. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997;

16: 173 - 176.

24. Livingstone M and Fraser IS. Mechanisms of abnormal uterine bleeding.

Hum Reprod Update. 2002; 8 (1): 60 - 67.

25. Sharma JB, Roy KK, Pushparaj M, Gupta N, Jain SK, Malhorta N and Mittal

S. Genital tuberculosis: and important cause of Asherman’s syndrome in India.

Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008; 277 (1): 37 - 41.

26. Grivell RM, Reid KM and Mellor A. Uterine arteriovenous malformation: a

review of the current literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2005; 60 (11): 761 - 767.

27. Halperin R, Schneider D, Maymon R, Peer A, Pansky M and Herman A.

Arteriovenous malformation after uterine curettage: a report of 3 cases. J

Reprod Med 2007; 52 (5): 445 - 449.

28.Shapley M, Jordon K and Croft. An epidemiological survey of symptoms of

menstrual loss in the community 2004. Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54 (502): 359 – 363.

29. Schlesselman JJ. Oral contraceptives and

neoplasia of the uterine corpus. Contraception 1991; 43: 557 - 579.

30. Narod SA, Risch H, Moslehi R, Dørum A, Neuhausen S, Olsson H, Provencher

D, Radice P, Evans G, Bishop S, Brunet JS and Ponder BA. Oral contraceptives

and the risk of hereditary ovarian cancer. Hereditary ovarian cancer clinical

study group. N Engl J Med 1998; 339(7): 424 – 428.

31. The Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study of the Centres

for Disease Control and the National Institute of Child Health and Human

Development. The reduction in risk of ovarian cancer associated with oral contraceptive

use. N Engl J Med 1987; 316: 650 - 655.

32. Ness RB, Grisso JA, Cottreau C, Klapper

J, Vergona R, Wheeler JE, Morgan M, Schlesselman JJ. Factors related to

inflammation of the ovarian epithelium and risk of ovarian cancer. Epidemiology

2000; 11: 111 - 117.

33. Mishell DR Jr. Noncontraceptive

benefits of oral contraceptives. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982; 142: 809 – 816.

34.Brinton LA, Vessey MP, Flavel R, Yeates D.

Risk factors for benign breast disease. Am J Epidemiol 1981; 113: 203 – 214.

35.The ESHRE Capri Working Group. Non contraceptive

health benefits of combined oral contraception. Hum Reprod Update 2005; 11(5):

513 – 525.

36. Brunner Huber LR and Toth JL. Obesity and oral contraceptive failure:

Findings from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Am J Epidemiol 2007;

1666: 1306 – 1311.

37. Curtis KM, Mohllajeea AP, Martinsa SL, Petersonb

HB. Combined oral contraceptive use among women with hypertension: a systematic

review. Contraception 2006; 73: 179 – 188.

38. Farley TMM, Collins J, Schlesselman JJ. Hormonal contraception and risk

of cardiovascular disease. An international perspective. Contraception 1998;

57: 211 – 230.

39. Lubianca JN, Faccin CS, Fuchs FD. Oral contraceptives: a risk factor for uncontrolled blood pressure among

hypertensive women. Contraception 2003; 67(1): 19 - 24.

40. Lubianca JN, Moreira LB, Gus M, Fuchs FD; Stopping oral contraceptives:

an effective blood pressure-lowering intervention in women with hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2005; 19(6):451 -455

41.Atthobari J, Gansevoort RT, Visser ST, de Jong PE

and de Jong-van den Berg LTW. The impact of hormonal contraceptives on blood pressure, urinary albumin

excretion and glomerular filtration rate. Br J Clin Pharmacol

2007; 63(2): 224 – 231.

42.Rees DC, Cox M and Clegg JB. World distribution of factor V Leiden.

Lancet 1995; 346: 1133 – 1134.

43.Blickstein D and Blickstein I. Oral contraception

and thrombophilia. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2007; 19: 370 – 376.

44.No authors listed] Intrauterine

devices: an effective alternative to oral hormonal contraception. Prescrire

Int 2009; 18(101): 125-130.

45. Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Steroidal contraceptives: effect on

carbohydrate metabolism in women without diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;

7(4): CD006133.

46. Cagnacci A, Ferrari S, Tirelli A, Zanin, Volpe A. Route of administration of contraceptives

containing desogestrel/etonorgestrel and insulin sensitivity: a prospective

randomized study. Contraception 2009; 80(1): 34 - 39.

47. Xiang AH, Kawoakubo M, Kjos SL, Buchanan TA. Long-acting injectable progestin contraception

and risk of type 2 diabetes in Latino women with prior gestational diabetes

mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2006; 29(3): 613 - 617.